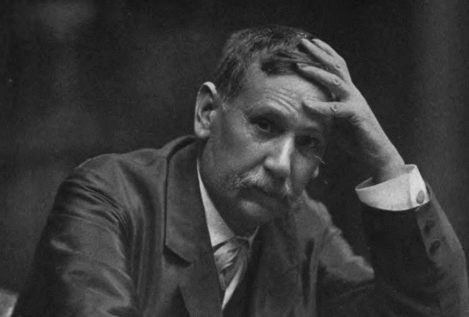

Lecuona, the Anti-Modern

«His name will be linked forever to ‘Malguena’ thanks to —or despite— its relative stylistic anachronism and its over-the top populism»

AP Images

Ernesto Lecuona (1895-1963), a composer whose birthday 125 years ago was celebrated last year, arrived in Spain in 1924 from his native Cuba to participate in a concert tour. Four years later he published a music book of pieces for piano titled Suite Andalucía which included five works that evoked his trip: ‘Córdoba’, ‘Alhambra’, ‘Gitanerías’ [Gypsy Themes], ‘Guadalquivir’, and the ultimately famous “Malagueña”. Capturing travel impressions in music had been a Romantic tradition with notable examples such as Années de pèlerinage [Years of Pilgrimage] (or Album d’un voyageur [A Traveller’s Album]) by Franz Lizst (a work in turn inspired by Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister) and the famous collections for piano by Isaac Albéniz, such as the Suite española, the Rapsodia española or the Suite Iberia. Nonetheless, in the 1920s, postcards from travel abroad were, to say the least, a stylistic anachronism that the majority of European composers could no longer afford. Thus, Lecuona, perhaps because he was born on the periphery of Eurocentric artistic life, far from Paris and Vienna, could afford to remain on the margins of what had occurred in the world of concert music in the previous forty or fifty years. The avant-garde, Debussy’s mists, Schoenberg’s cacophony, were alien to him. Without making it explicitly clear or, much less, theorizing about it, Lecuona chose to be —or perhaps life led him to be— an anti-modern composer.

Born in the town of Guanabacoa of a Cuban mother —who contributed financially to the cause for independence— and a father fom the Canary Islands, an astute and cultivated journalist, responsible for several influential newspapers on the island, Lecuona grew up in a family of musicians (Ernestina Lecuona, his sister, was also a composer of note), and he stood out as a child prodigy. He gave his first piano concerts at the age of nine and debuted in New York in the Aeolian Hall at the age of sixteen. Later years saw him give numerous concert tours in Europe (Salle Pleyel and Salle Gaveau) as well as in the Americas (Carnegie Hall), an activity which only ceased near the end of his life.

As a composer, nonetheless, Lecuona sought and found a language in his own tradition, in that of his home, so so speak. The so-called ‘danza’ (dance) was a salon genre for elegant, European-loving society in Cuba. In some cases the danzas were suitable for amateur performers, but they were, above all, ideal for semiprofessionals, generally speaking, women with years and years of conservatory training but who were devoted to family life. The great precedent for this Cuban style was the work of Ignacio Cervantes, whose compositions which, while fitting into the moulds of European salon music, creolize this music through syncopation, or unexpected accents, which are, of course, echoes of Africa. The danza —like the US ragtime or the Brazilian choro—, while are cast in European moulds, takes African elements and mischievously impregnates, tinges and hybridizes certain genres of European salon music like the march and the waltz.

What’s more, Lecuona, in the interwar period, found the perfect intellectual frame in the Afro-Cuban movement led by Fernando Ortiz and Nicolás Guillén. His Danzas afrocubanas (1934), another music book for piano, are the fruit of his recognition of these roots. But, in this case, they are removed from the Romantic European postcard from abroad and their titles reveal the source of their inspiration: ‘Danza de los Ñáñigos’ (referring to a secret Afro-Cuban society), ‘Danza Lucumí’ (alluding to santería cults which syncretize Catholicism and various African religious practices), and with more explicit references, ‘Danza negra’ [Black Dance], ‘La comparsa’ (The Carnival Krew), ‘La conga de medianoche’ (The Midnight Conga Line), and finally, ‘Y la negra bailaba’ (And the Black Woman Danced). Clearly, his European father was fading and his Cuban mother, the independentista, was coming to the fore.

Another advantage of being on the margins of the avantgarde and its explicit aesthetic elitism was his acceptance of the genres of commercial music. There is a great fluidity in Lecuona between the high and the lowbrow. For decades his creativity followed the same process in bringing a work into being. Since he was a virtuoso of the piano, almost all his works began as compositions for piano which he later gathered into successive collections (that was the case of the Suite Andalucía). Now, some of the individual works contained in these collections could be converted into pop songs. That was the case of ‘Malagueña’, which was, possibly, inspired in the version that Albéniz did of the flamenco singing of Juan Breva (Breva of whom García Lorca quipped unkindly that he possessed a «cuerpo de gigante / y voz de niña» [a giant’s body/ and a little girl´s voice] and which ended up in the US as a fox trot titled ‘At the Crossroads’.

Other big-hit songs of his, like Siboney or Siempre en mi corazón (nominated for an Oscar in 1942 under the title Always in My Heart), had their origin in zarzuelas [Spanish operettas] and musical revues, another genre he cultivated from youth and very assiduously. Later these were incorporated into movies and made popular by pop singers of different generations. Para Vigo me voy [To Vigo I go] (sensibly recuperated twenty-five years ago by Compay Segundo), was known as Say sí, sí, but in the hands of the Andrews Sisters it had already sold more than a million recordings in the forties. Like George Gershwin, with whom he is often compared, Lecuona is a composer who regards the commercial world without prejudice. His model —that fluidity between the high, the middle and the lowbrow —has been duplicated many times by those who came afterward, by Ástor Piazzolla, for example.

Some years before he died, Lecuona returned to Spain, feeling, some say, the prick of nostalgia for his Spanish roots. In 1963 he received a heartfelt tribute from the city of Malaga. He would die a few months later in Santa Cruz de Tenerife, but he is buried in Hawthorne, a town in the vicinity of New York. He had renounced Castroism and promised not to return to the island until the end of the regime, making his home in the end, like so many Cubans, in Florida.

His name will be linked forever to ‘Malguena’ thanks to —or despite— its relative stylistic anachronism and its over-the top populism. The song kicked off the fashion for latunes, as some critics call them, which is to say: pop songs with a generic Latin rhythm but with lyrics in English and which have no hesitation in taking on cultural allusions —to the Latin Lover , the Latin bombshell —or to Spain, Portugal, Brazil, Cuba and the rest of the countries in the Americas. ‘Malagueña’ was recorded as light jazz by Jimmy Dorsey’s big band, and subsequently it was sung by Bing Crosby and Plácido Domingo; Liberace and Paco de Lucía have played it, and Keith Richards let it be known that it was the first guitar piece he had learned. Ah, and in the fanciful film Once Upon a Time in Mexico, Johnny Depp takes the full hit of a pistol wielded by Eva Mendes—a bombshell if there ever was one—to the tune, of course, of ”Malagueña” in its techno versión. Maybe Lecuona has proved to be more modern than we thought.