Exiles: With One Foot in the Unknown

«For thousands upon thousands of those intellectual emigrés after the different conflicts, and after frightening persecution, wars of destruction and extermination, that interminable exodus would end up consuming them altogether.»

“We had set one foot in the unknown, without knowing for how long it would be or what consequences it would have for our own fate or for that of all humanity,” is how Monika Mann, Thomas Mann’s daughter will put it in her Diary, as soon as they all reach the first part of their exile in France’s Provence. It was 1933. Hitler had just risen to power, and that immediate and troubling sense of being pulled up by the roots, taken at first to be an uncertain episode, an unsettling parenthesis, but not the apocalyptic one it would really turn out to be, was little by little taking on a definitive quality. For Spaniards, for Germans and Austrians, for Russians exiled after 1917, the separation from their homeland would last too long. It left deep wounds for which there was no consolation, and for many the return to the land they had left was never a possibility.

Specifically, for thousands upon thousands of those intellectual emigrés after the different conflicts, and after frightening persecution, wars of destruction and extermination, that interminable exodus would end up consuming them altogether. A certain number of others, who were more resilient or whose luck, along the countless bends in the road, was more benevolent, would go on creating and writing with renewed energy. There was no reason for creativity to come to a halt. On the contrary, the message sent directly to the executioners, to the tyrants and murderers of freedom in those times had to be clearer than ever. Freedom was a possession impossible to hunt down. In that struggle without quarter there was no room for defeat. The fight looked well-nigh eternal and must never flag.

Like all those refugees from Nazism, Monika Mann would add her especially unhappy events to the collective story. Once she and her family had fled from Germany, she went to Florence to study music and there she would meet a brilliant Jewish intellectual, the Hungarian refugee, Jenö Lányi. Because of the racist, anti-Semitic laws in place in Italy, both were forced in 1939 to leave for England, where they married. In 1940 they secured a visa to emigrate to Canada, but during the crossing from Liverpool to Quebec on the City of Benares, the boat was torpedoed by a German fighter plane. Her husband was drowned, together with 258 other people, among them 90 Jewish children sent to Canada for safety by their European families. Monika would be rescued and taken to the United States, where her parents were already settled.

As I wrote my book, Sin tiempo para el adiós (exiliados y emigrados en la literatura del siglo XX)[No Time for Goodbyes (Exiles and Emigrés in Twentieth-Century Literature], hundreds of personal stories from those exiles would leap out at me, and bring tears to my eyes: stories that were often heart-rending, fateful appointments with destiny and surprising encounters taking place in the most unexpected corners of those infinite roads of the Biblical exodus. Encounters, dialogues at the very gates of hell, or in paradises eventually found, crisscrossing one another. Conversations that spoke incessantly of different futures. From instants that were often fleeting they spoke with the eloquence of great lessons, left in legacy to a future that would one day be capable of understanding them and endowing them with the tragic significance that they, those who fled, hardly had time to recognise, as they escaped and saved their lives, without stopping. Without time for tears or heartfelt goodbyes or makeshift farewells. Later the memory of the survivors would return those instants to them like breath released, to a place in history, a great and indelible History written in capital letters, that would keep them forever. Sometimes the words were rough, offensive, tripping off the tongue with the arrogance typical of brutal and barbarous times. The words were sometimes almost spit out to honest representatives of a humanism then on the run. “Tell me, honestly. Why is such fury unleashed on me?”. That was the question put a French civil servant in the Vichy government by the brave young American hero Varian Fry, who was responsible for a legendary rescue network in Marseille, during World War II. The fascist oficial with an aristocratic name, Maurice Rodellec de Porzic, looked at him disdainfully and answered curtly: “Because you protect the Jews and the anti-Nazis.”

Not too long before, this pretentious representative of “the new France”, who had been put in charge of the prefecture of Marseille in 1941—and whose arrogance was common to all the enthusiastic Nazi collaborators in the terror that had spread across Europe—, this same haughty public servant who invited Fry to quit French territory, told him cynically: “I know that in the United States they still support the old idea of human rights. But they will come round to our point of view: it is only a matter of time.”

«For Stefan Zweig Europe was always the closest thing to a faith, to an inalienable religion.»

Two worlds: the free world and the conquered world, in alliance with totalitarianism, worlds which at the time, when Fry and the French official were talking in the latter’s office, were beginning to group and square off against one another in military alliance, as the Allies and the Axis Powers. Two sides, within a new European world war, of consequences still terrible and unknown, as frightening as the warning signs were from day to day in Nazi-occupied France, which at the time were still taking a definitive shape. At the same time, and paradoxically, the best part of the fortitude of the supposedly weak and defeated was reborn time and again. That is, the humanist rebellion against barbarism was reborn. It was the eternal struggle of Calvin Against Castellio, of despotism versus freedom, as Stefan Zweig wrote in his memorable essay. For Zweig Europe was always the closest thing to a faith, to an unrenounceable religion.

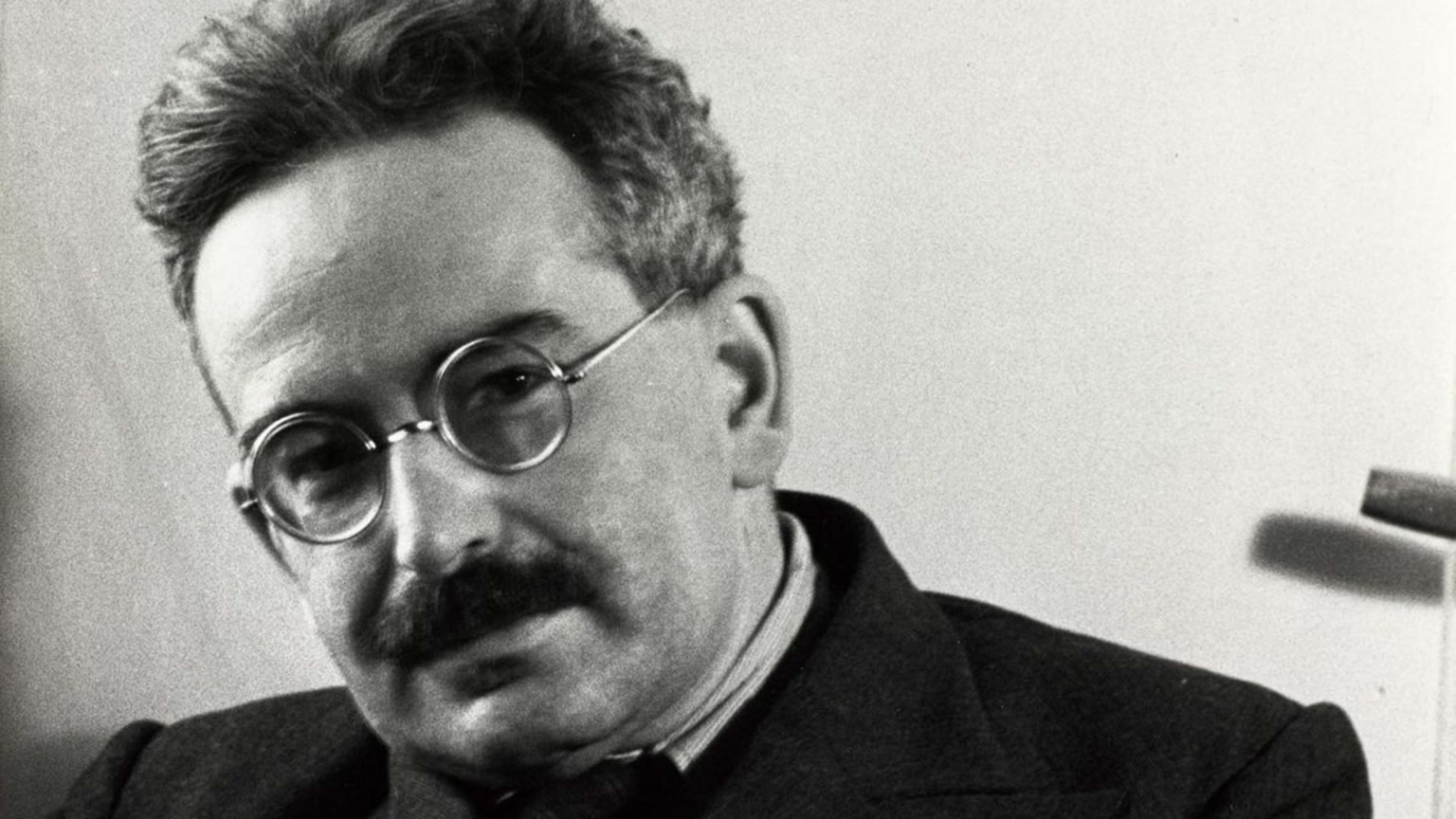

Weak, tired, persecuted and put down without mercy. In so many cases, tired of fleeing. Of running from one war and then another, in wars that would link hands in death, as was the case for so many Spaniards who took the path of exile and no sooner crossed the border than were corraled into cruel concentration camps, in the open air, in the dead of winter, on beaches in the south of France like Argelès. Or German and Austrian democrats who on finding themselves caught in the mortal trap of a collaborationist France, where one day they thought they were safe, were also shut away overnight in humilitating internment centres. That is what happened to Walter Benjamin, Hannah Arendt and so many others.

One day before the German army entered Paris, on the 13th June 1940, Benjamin had left the capital for Lourdes. From there he set out for Marseille and finally arrived at Port-Vendres in southern France, with the intention of fleeing to Spain. As soon as he got to that little coastal town in the Eastern Pyrenees, he went immediately to find the contacts he had been given: Hans and Lisa Fittko, two Germans from the Resistance whom he knew already and who could help him cross the border. Walter Benjamin was 48 years old at the time and suffering from various health problems, including a chronic sciatica and above all, miocarditis in the heart.

Lisa Fittko, who was known for a long time as the “invisible heroine of the Resistance”, just as could be said of young Varian Fry, would write some passionate memoirs of that overwhelminlgly important part of her life as a “border crosser”. In them she would devote a sad and affectionate chapter (“Old Benjamin”) to the death of her friend whom she had met again and lost shortly thereafter. A moving encounter that she would never forget and which, many years later, would lead readers like me to write up the memoirs of those “stolen instants”. Of those appointments with destiny “and all Humanity`s”, as Monika Mann said. At the time, it was September 25, 1940 and everything was happening in a cramped little attic in Port-Vendres. Lisa had gone to bed a few hours before when they knocked at her door. On opening, she saw that it was one of her friends from Berlin, Walter Benjamin, who, like so many others, had sought refuge in Marseille when the Germans invaded France. The words spoken by “Old Benjamin”, as she called him, could only astonish her: “Dear Madam”—said Benjamin, who at that moment represented the universe of yesteryear — “I beg you to forgive me for disturbing you. I hope I have not come at an inconvenient time. Your husband explained how I could find you. He told me that you would take me over the border to Spain”. Fittko could not get over her amazement: the world was collapsing, but Benjamin’s courtesy was proof against all change.

To put this another way, it was a matter, once again, of two worlds that had come into contact: the combat defined by Stefan Zweig in his novel The Chess Player, a pessimistic allegory of Nazism, with its brute force and the implacable advance of a destructive stupidity, showing no mercy toward brilliant and intelligent minds, respectful of the human forms of other times. Or, if you like, it was the world of Calvin Against Castellio, despotism versus humanism, which symbolically met at two instants of misfortune. On the one hand, the arrogance and contempt with which the collaborationist bureaucrat of Vichy challenged the young hero, the envoy from the free world, Varian Fry. And on the other hand, the courtesy with which Walter Benjamin, old, weary, and with impeccable delicacy, asked, politely, if he had not put his “border crosser” out at that precise moment and at such an inappropriate hour. “The old idea of human rights”, as we now know, thanks to those free spirits who spoke to the future, would once again emerge triumphant.