Spain and its Fiction (and essay)

“Galdós sees himself in Spain and Spain, whether it knows it or not, has seen itself in Galdós for a century-and-a-half, and that mirror has not yet been broken or entirely tarnished”

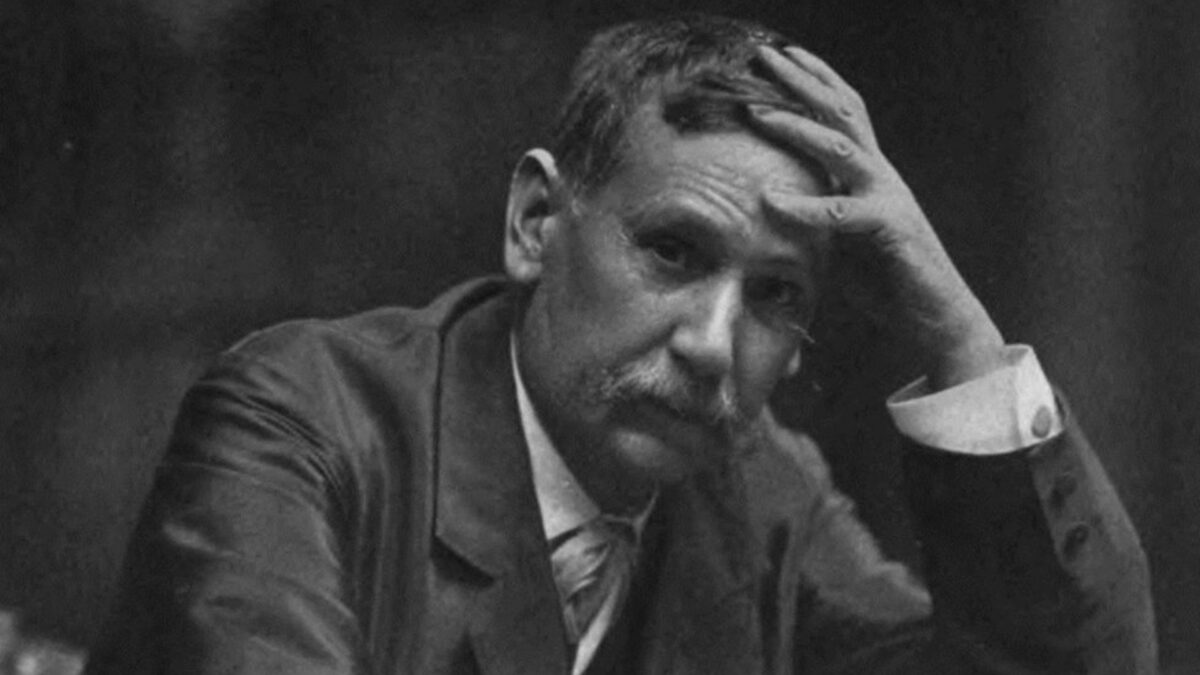

Wikimedia Commons | Wikimedia Commons

Several months ago a Sunday paper asked a long series of writers and other intellectuals to propose the name of the writer who best represented our country’s virtues and defects. A writer who would be a symbol or a metaphor, something in the manner of Dickens in England or Balzac and Zola in France. I hesitated. I thought of Cervantes, I thought of Pío Baroja, I thought of Benito Pérez Galdós and then I started ruling names out. Cervantes had set the bar too high if you take him to be a writer symbol.

So much so that they had to come in from outside (the British) to tell us not only that he was good, he was the best. (This keeps happening: it happened with Marías in Germany and France and with Vila-Matas in Latin America and then in France.) But being the best does not mean being the one who best represents us if we are not, approximately, the same in stature. And we are not of the same stature as Cervantes. Then it was Baroja’s turn and I ruled him out too: although he was the Generation of ‘98 novelist who had brought the most European literature and philosophy into Spanish fiction, his ímpetus—not his mastery—had declined with time.

The finalist and winner of the honour was, therefore, Galdós. Galdós, who in his literature lays the basis of contemporary Spain in the wake of the 1812 Constitution; Galdós, who is the one who best portrays precisely some of the virtues and the majority of the vices that have configured contemporary Spain. Galdós sees himself in Spain and Spain, whether it knows it or not, has seen itself in Galdós for a century-and-a-half, and that mirror has not yet been broken or entirely tarnished. Therefore we speak of his work, but –what about him?

If we turn to Baroja we find a Galdós —“trouble-making and somewhat underhanded in his ways”— who “knew very well that in his Spain, just as in ours, there was nothing and nobody who could hold his own and that the solicitous hand of the author was needed to defend his own work”. This business of the author defending his work seems to obey an overwhelming logic because in the majority of cases it’s not his contemporaries who are going to defend it: maybe those who come along a couple of generations later will do it, but almost never his peers.

But Baroja is not referring to that. He adds: “Galdós, whenever he published a book, lavished attention on the critics, he wrote letters to the editors of newspapers in Madrid and in the provinces, some of them handwritten, flattering them, feigning humility. I have seen two or three of these letters”. And after taking him to task for having few scruples and insisting that in this way he opened himself to being “blackmailed by many…and asked to give money away left and right so that they would let him be”, the Basque author passes judgement —for a judgement it is: this lack of ethical sensibility makes Galdós’s books, which sometimes achieve great technical and literary perfection, fall short of the mark. Chiefly it is what causes his works not to come up to those of Dickens, Tolstoi or Dostoievsky. There is no flame. No generous spiritual ebullience. “And if in literature”, says Baroja,” one can be a cynic or a degenerate or an egotist, what he cannot be is a smart-aleck who seeeks to conceal his little tricks and intrigues from the eyes of the public”.

On reading these pages from Baroja’s Memoirs, and bracketing his ill humour, or his truthfulness in part or overall, together with the rivalry, imaginary or real, which he felt toward Don Benito, I concluded, unfortunately, that they did not tarnish but rather reinforced my choice of Pérez Galdós as the author symbol or author metaphor of our country. If we exclude the business of throwing money about, it suffices to take a quick look at the issue, from up close or far way, it does not matter. And that does not mean that we cannot enjoy reading Pérez Galdós as well as Baroja, which is important because literature is not sectarian —or it should not be—, and there is too much proof in Spain not only that it continues to be but that the levels of sectarianism have risen considerably in recent years. As in politics, so in culture, because it is in culture that things happen first —frivolously, many times, or pitching from one side to the other— and then they creep into politics and society at large. To judge writers as conservatives or progressives, old or modern —as we continue to do— and to overlook their lapses into venality —material or intellectual— or their unworthy manoeuvres or their passion to hold certain areas of power, continues to be a physician’s report that uncovers some maladies we have not been able to rid ourselves of, despite our having entered into modernity decades ago. The same maladies that Galdós, in sickness or in health, knew so well how to portray.