José Antonio Zarzalejos: “If the outcome of the Juan Carlos I case is handled well, the parliamentary monarchy has a future”

Daniel Capó speaks with Zarzalejos about Juan Carlos I’s difficult legacy, the need to accept the inviolability of the king, Felipe VI’s role during the ‘procés’ and future reforms that Spain needs to undertake

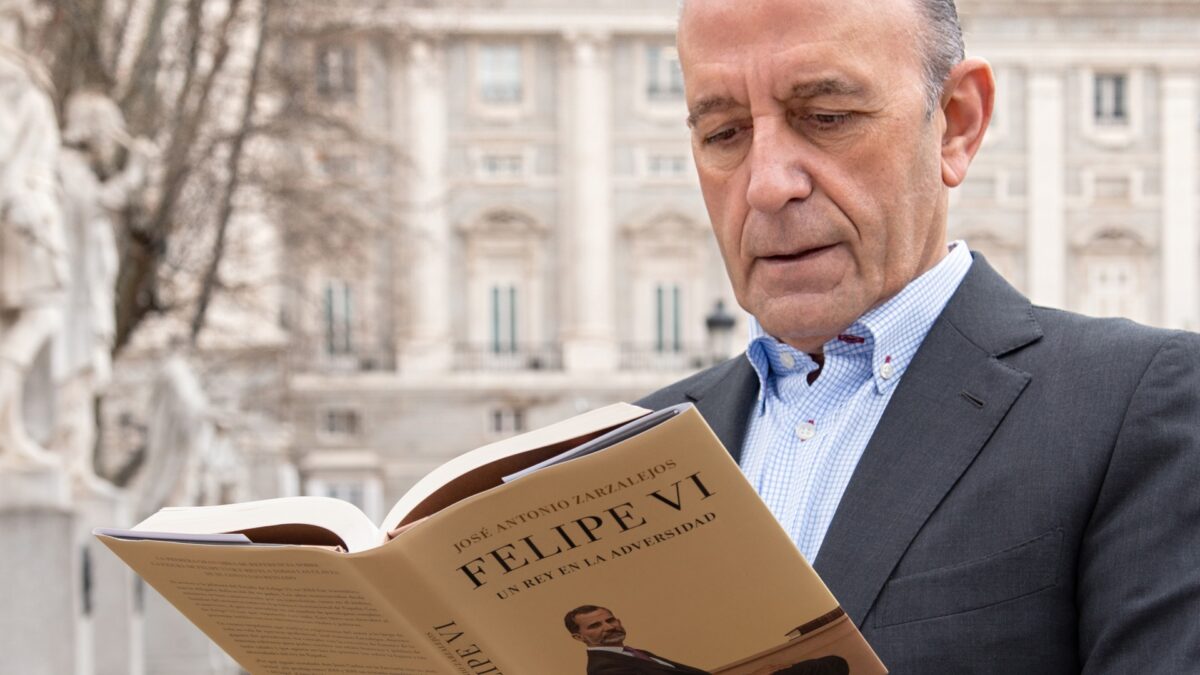

Editorial Planeta

In his recent book Felipe VI. Un rey en tiempos de adversidad [Felipe VI. A king in times of adversity [ed. Planeta]) José Antonio Zarzalejos (Bilbao, 1954) draws a portrait of the intense years of the monarch’s reign. It is a book written in favor of the Crown, conscious of its enormous historical importance, but which does not conceal the tremendous difficulties that the Crown is facing at the current political juncture.

In this long conversation for The Objective, José Antonio Zarzalejos reflects on Juan Carlos I’s difficult legacy, on the need to delimit the monarch’s inviolability, the role of Felipe VI during the procés [Catalan independence process][contexto id=”381726″], and future reforms that Spain needs to undertake.

In an earlier book, Mañana será tarde [Tomorrow It Will Be Too Late], you devoted a chapter to “the colors of corruption” and you came down particularly hard on the role of city governments. “Municipal corruption is the most pernicious”, you declared. In this book, devoted to King Felipe VI, you do not mince words in describing his father, the King emeritus. Do you still believe that corruption seeps up from below, as you suggested in Mañana será tarde, or on the other hand, do you now suspect that it is a more transversal phenomenon that plagues all the different levels of Spanish society in equal measure?

I based that 2015 essay on an empirical criterion: local administrations —with less oversight — and political parties are where the greatest cases of corruption have been recorded. This criterion continues to be perfectly valid, although corruption —and this is pointed out in the book— is a heterogenous phenomenon and crops up at every point. But it is linked to the way in which contracts for public works and services are approved and awarded and it is subject to the trafficking of influence. This continues to be the case, although in recent years there has been a more regenerative reaction. The presumed corruption of the former King does not fit into the usual scenario. On the contrary. It occurs in the echelons of the Head of State and it rests on a constitutional privilege granted for the full exercise of the Head’s functions: inviolability. The concept refers to the “person” of the King’s inaccountability before the law and, according to the current majority interpretation, it protects the institutional decisions and conduct of the Head of State in the exercise of his office, but it also applies to decisions and conduct sustained in his private life. It offers complete immunity, which, in this case, has served as an instrument for impunity. No term of comparison can be established, therefore, between this and the political corruption I referred to in Mañana será tarde.

In the book you are especially hard on Don Juan Carlos, whom you accuse of dragging his son and the Royal House down. At what point did you grow suspicious of him? And when did you realize that his performance could eventually destabilize the heart of Spain’s constitutional system of government?

I am not hard on the former King in the book Felipe VI. A King in Adverse Times. I am simply being descriptive and that description turns out, in effect, to be tough because the facts that are being recounted are tough. I perceived that Juan Carlos I’s behavior could be destabilizing for the Institution when the former King lived too close the various incidents of the “Noos case”, which impacted directly on his son-in-law and his daughter. The accident-ridden hunting expedition in Botswana indicated that the King should withdraw from the office of Head of State because of the sudden collapse of his reputation..Not even his request for a pardon —so inappropriate in word and in manner— could forestall his abdication, which is the only procedure available to reigning kings to clean up their political responsibilities. But the point when I noticed that the abdication had thwarted its capacity for good was in June 2919 when Juan Carlos removed himself (was removed) from the public agenda and his secretary’s office in the Royal House was closed. I was put on guard by how brusquely the decision was taken and that was when I began the inquiries in this book. From that day onward it was all an almost unique sequence of events that called attention to inadmissible behavior on the king’s part, which put Felipe VI in an extremely difficult position; these problems were addressed with intermediate measures, up until the radical measure of expatriation was taken, pending the formal initiation, on June 5, 2020 of the investigative and penal proceedings by the Ministry of Finance in the Supreme Court’s Second Chamber, which are still under way.

With the scourge of so many scandals, and beyond what the polls say, do you believe that there may be taking place a slow but sure shift in the opinion of Spaniards that would lead them away from the monarchy to a republic? What is your gut feeling about this?

If we situate this matter in the area of “gut feelings”, mine is that in Spain there is neither a republican utopía nor a consensus for the monarchy. Those who are prescribing a Third Republic are not fighting against the parliamentary monarchy but rather the system and they are thoroughly mistaken. They haven’t learned anything from the Republican utopía of the 1920s and 30s. There is no consensus over the monarchy, but there is a pragmatic sense of society’s priorities and initiating a constitutive process for a new system is not among them, And that is what is required to move from a monarchy to a republic. If the outcome of Juan Carlos I’s case is handled well, the parliamentary monarchy has a future. What I am certain of —and this is not a mere gut feeling— is that there is a core citizen demand: to set limits to the King’s inviolability; a subject that requires profound legal reflection on the way to tackle this kind of limitation, and another kind of reflection — political-institutional— that brings in other legal and constitutional institutes as the guarantor of the King’s actions.

Faced with this difficult legacy, you point out that Don Felipe has felt obligated to “rebuild all that his father, after building, destroyed”. Do you think that toward that end it might be necessary to prepare a law that allows for the regulation, the sooner the better, of certain aspects of the Royal House?

The law of the Crown is a political and journalistic creation. Some legal experts think it is possible; others deny that Title II of the Constitution allows for it. At present it is not viable because it would open a debate that would go beyond the purpose of establishing a kind of statute for the King. I prefer to think of transferring private provisions for the royal family into Royal Decrees and that a measure having to do with transparency become part of the code of conduct for the employees of the Royal House. And I would like to see a debate —once the health and economic convulsions are over, as well as the Juan Carlos I affair— about how to tackle the inviolability of the King. We have been warned by the Professor of Penal Law, Enrique Gimbernat, since 1977, that the possibility existed of “a delinquent monarch”— and the warning went unheeded because the Constitution lined up, on this point, with other European constitutions.

And, on another score, would you consider it a good idea in the present political scenario to establish a parliamentary commission to investigate the activities of the former King?

In general parliamentary commissions in Spain are pointless. The groups have not known how to implement them properly and they lack historical grounding in society. Besides, they tend to run parallel to judicial investigations—in this case fiscal ones—, which makes them almost meaningless. For the rest, a commission that investigated the former King would have to cease all activity, according to legal counsel in Congress. as soon as the inviolability of the King came into question. Most definitely, it is better that the State Attorney General finishes the job and that we find out which conduct on the part of the former King has been investigated and if all of it is covered by inviolability, if relevant laws have expired, which fiscal activity has been voluntarily regularized and, alternatively, if there is behavior that, has no protection under those umbrellas,and merits penal action before the Second Chamber of the Supreme Court, where the King has immunity from prosecution.

On p. 131 of your book, you claim in a passage with quotation marks around it that in the Zarzuela Palace they take very seriously the risk that Corinna Larsen poses, whom they consider to be a “terrible enemy” of the institution. In your opinion, is this danger limited to the question of fiscal fraud or might there be other unforeseen ramifications, including some of a political or diplomatic nature?

I think that the “fear” on the part of the Royal House with respect to Corinna Larsen has to do with the former king’s conduct but that it has no ramifications of a political or diplomatic nature. There are some paranoid-conspiratorial theories about this, but the reality is that the relationship between Larsen and the former king was very personal in nature and extended to money and financial operations in which this lady had almost professional experience.

The book devotes several pages to the “procés”[Catalan independence process] and the historic speech that the king delivered on October 3, 2017. It was a speech, you say, “that was well-received outside of Catalonia, but not there”. Nonetheless, it does not seem that it was well-received among the ruling political class in Spain, inasmuch as neither Rajoy nor Sánchez openly applauded it but, rather, expressed some reservations about it in private. There is something dramatic in that picture of a man, by himself, with all the weight on his shoulders, representing the Crown, faced with an historic moment. What significance did this speech have for the King’s image? And how do you think it will be judged in the future?

The events that took place between 2017 and 2021 are turning out to show that the King was right in his speech. Rajoy’s indolence, his failure to manage events in Catalonia, and the King’s constitutional responsibilities (he represents the unity and integrity of the State) supported him in that speech. Rajoy did not like it because it showed up his own omissions; neither, obviously, did the independence forces or the bourgeois and plutocratic Catalan bourgeoisie, which has well and truly been “hijacked” by the utopía of statehood. Nor was it welcomed by that vein of rather forced sentimentality on the part of certain Catalan strata who clamor for “affection” when what they mean is “money”. The King was where he was supposed to be in a crucial situation and he avoided a vacuum arising in the presence of the State after a failed intervention on October 1st. His speech on October 3, 2017 has been an asset for Felipe VI and it will be more so as time goes on. Let’s look at where Catalonia is at present,after the elections on February 14th, and reread the King’s words in that light. They regain sense and relevance. Felipe VI is a man who can be extraordinarily resilience, as he was during this episode; and he remains convinced, justifiably so, that he acted as he should.

In the book you also point out that the King was better informed than the government about the reality of Catalonia, despite the State’s enormous intelligence and information-gathering apparatus. How is that possible? Should we attribute that exclusively to Rajoy and his team’s indolence or does it suggest a deeper deterioration of the functioning of institutions?

The King, in his modest margin for autonomy, keeps up to date with information about matters that affect the State and Spanish society. By constitutional mandate he must receive that information; he is present in the State’s most sensitive organisms of information and he carries out an intense activity of active listening. Many different spheres of activity are open to him— political, business, academic—and he is a man who absorbs information and reformulates it. On the subject of Catalonia he was always better informed than Rajoy and, above all, he drew more valid conclusions than the Government. He always thought that the self-rule procés was headed for collision and Rajoy thought that it was about negotiation.

Thinking in the long term, I would like to pose two final questions. The first is that the book gives off a certain air of conviction that a federalizing reform may be the mechanism that allows the current crisis to be contained. But a skeptic would reply that hardly anybody in Spain knows what a federal State really is and, on the other hand, and perhaps even more importantly, that there are hardly any federalists among the nationalist parties on the periphery.

I think that our Constitution’s future is a federal one. The autonomic model is a dense and sticky one and nationalists and proponents of independence like it because its limits are diffuse. A federal State is much clearer about jurisdictions, more demanding in terms of cooperation, more solid as a single entity, freer in its plurality and difference and easier to implement because we have at our disposal comparative constitutional law and also practices and customs that are equally comparative in nature, from which we can learn and with which we can experiment. There are centralized states, regional and federal. But the autonomic state is a rare beast and it ought to be transitional. Spanish doctrine is full of federalists, but to the right Federalism spells dispersion and the left is inhibited because the different nationalisms with which it collaborates so intensely do not want to hear of it. The third Spain is federalist as was Salvador de Madariaga, a point of reference for federalism in Spain.

And, finally, I would like to ask you about the future of the Crown. What do you think it will look like in twenty or thirty years? How do you think the institution will have changed and where might it be headed?

First, there will be parliamentary monarchies, and they will continue to be efficient if they are constantly updated, maintaining their traditional legacy that identifies their society’s past and projects them toward a shared future. Even more so if instead of a King, Spain has, as I think it will have, a queen unconnected with the transition and her grandfather’s reign, in these past years. For the rest, the prescription is already written; exemplary behavior, transversality, a point of reference for civic and democratic values. The king or queen is a civil servant with certain demands, some of them extraordinary, placed upon him or her, whose fulfillment is indispensable, in order to make up for the eccentric bias in a democracy of an hereditary institution. Most definitely: not all that is elected sums up what is democratic, but what is not elected must comply with the traditional functionality that the Constitution charges it with in a way that is permanently praiseworthy.