Naturally Spanish

«It is not very elegant to boast of doing the right thing. In any case, what applies in Rhodes’s case is the privilege accorded fame, and that should bother us all, including him»

Wikimedia Commons

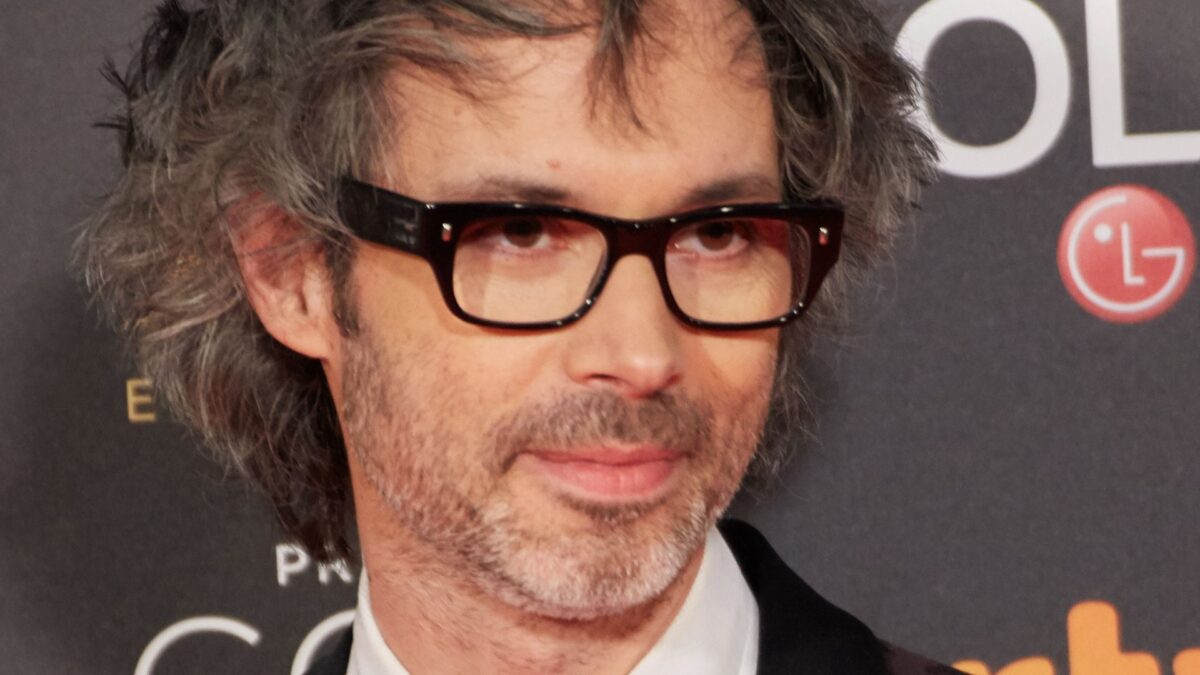

A little over a month ago James Rhodes, the ‘musician, writer and occasional activist for children’s rights’ —the definition is his—, obtained Spanish nationality through a carta de naturaleza (letter of naturalization), which is one of the ways of securing a Spanish passport reserved for exceptional circumstances, sports players, scientists, and so on. Rhodes has worked closely with the current government on the new Law for the Protection of Childhood and has been received by President Sánchez. He has also cheered on the second vice-president in his Twitter account and has even introduced him to David Simon, creator of The Wire, a series that Iglesias is now watching for the second time. It runs for five seasons. Rhodes is also a pianist; he fills concert halls and his books fly off the shelves. He has something of the mystic about hin: he speaks so softly, he seems so likeable, and at the same time there is a terrible story in his past, a tragedy, that led him to self-destruction and, finally, to a triumphant cure thanks to music. His story is edifying, even if his book Instrumental is middling.

On hearing the report that he had gained Spanish nationality, many immigants saw fit to recall how difficult the process is for normal people. It is slow, driving one to despair and, as the writer Margarita Yakovenko has said, the easiest way to solve it is to pay to have all the red tape go faster. There were those who took advantage of the media coverage of the pianist to denounce the bureaucratic backlog that encourages a black market in appointments. On Twitter James Rhodes received contemptible insults which, more than sullying the pianist, describe their author. Pablo Iglesias claimed credit for the granting of Spanish citizenship to Rhodes, although in a subsequent tweet he no longer seemed to form part of the government or to be able to do anything to speed up the process of naturalization of thousands of residents who are awaiting a decision on their applications.

This past Sunday James Rhodes published a sorry column in which he stated that the criticisms he received —for obtaining Spanish nationality the way he did— stem from envy, but that he felt more Spanish that way. The national flaw in Spanish character, as the actor Fernando Fernán Gómez once explained, is not envy but contempt and, as these lines reveal, in that respect Rhodes seems to be integrated. ‘I have paid a staggering amount of taxes and I have done everything possible to improve the life of my countrymen, be they friends or perfect strangers’. Which is to say, he has done what the law required him to do, as far as taxes are concerned. Like a majority of Spaniards and residents, he has complied with his obligations. It is not very elegant to boast of doing the right thing. In any case, what applies in Rhodes’s case is the privilege accorded fame, and that should bother us all, including him.