The Man Who Lived With Himself

«The mystery of cycling is the mystery of man, who lives with others and depends on them,but in the end it’s his own strength that counts. Because at the moment we call the decisive one, you find yourself alone with destiny»

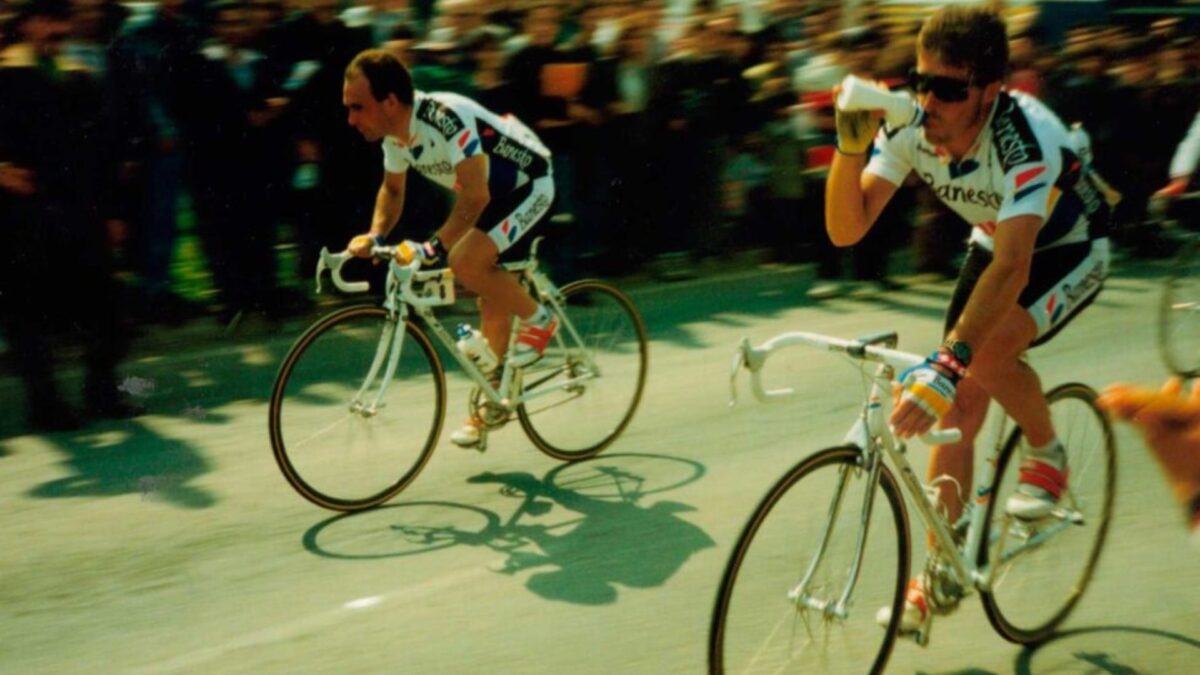

Flickr

For those of us who were born in the sixties, cycling came into our lives like a comet from out of the blue. The sport had been reduced to the perimeter of a football field or perhaps —as was my case— to a tennis court, since my mother is Swedish and those were the years when Björn Borg inaugurated the IKEA aesthetic. But cycling was unknown to us and so it remained until, at the start of the eighties, television began to regale us with the stages of the Tour de France and the Vuelta a España [Tour of Spain], with names —now mythic— like those of Ángel Arroyo, Perico Delgado, Alberto Fernández, Álvaro Pino, Vicente Belda or Marino Lejarreta, who in the imaginary of Spanish fans replaced the names of Bahamontes, Ocaña, Poblet, Julio Jiménez or the brilliant Tarangu. It was television that set off this fervor (I remember that the first stages I saw were those of the Tour in which Ángel Arroyo came in second, and the Spanish Vuelta that Alberto Fernández lost to Éric Caritoux), but it was the radio, above all, in its hour-by-hour news bulletins, with that unforgettable «Onward, friends» and the unmistakable voice of Javier Ares on Antenna 3, broadcasting the different stages of the race.

Javier Ares —who was at the time very, very young— is and has been the great inventor in Spain of cycling sportscasts. And as usual in these cases, he has had a great many imitators, much to the listeners’ dismay, who very quickly discovered that no copy can outdo the original. We know that, when it comes to art, mannerism has not yielded much fruit, and Javier’s way with words had little to do with mannerism and much to do with creation. His Spanish was impeccable, precise, clear and transparent, without sacrificing, once in a while, a baroque flourish that reflected the intensity of cycling, its epic side, I mean. He was known to bring a powerful imagination to his style, which lit up the reality of the race and projected it to sublime heights. A champion became a Colossus: a member of his team, a mythological figure. Petrarch’s poetic genius dwelt side by side on the ramps of Mont Ventoux with the cunning of Ulysses or quixotic Spanish largesse. He might describe cyclists as patricians of the bicycle pedal, only to go on to recall El Tarangu’s climb up the Tre Cime di Lavaredo or the elegant figure an Anquetil cuts. I am convinced that Javier Ares’s imagination was and is an imagination reeling with literature, conscious of the infinite possibilities of human creativity. I don´t know if he was «a pallid boy/ made sad with the sadness of one who dreams/ of days of glory» —as Miguel de Unamuno wrote—, but I am certain that he was a boy who lived long hours at a time with himself in the realms of fantasy, beside a book, listening to the transistor radio or playing with his friends and siblings in the back yard of his house. To live in one’s inner world seems to me the stamp of true personality, not borrowed or second-hand, and Ares was this and much more: a radiophonic creator who rose to the heights demanded of epic cycling.

I speak in the past tense when I ought to be speaking in the present; Javier Ares continues to relay the races and forms a wonderful duo with Alberto Contador. But that is the privilege of memory. My little boy listens to him avidly on the TV or on his YouTube channel, as he draws the outlines in a little notebook of a tour with no rhyme or reason to it, an imaginary geography that links the Iseran pass with the Tourmalet pass or the Gavia climb with the one in Lagos. Sometimes, when we go out for a ride in the mountains, I explain to him that the mystery of cycling is the mystery of man, who lives with others and depends on them,but in the end it’s his own strength that counts. Because at the moment we call the decisive one, you find yourself alone with destiny. Javier, my son, smiles as if he does not quite get what I am talking about. And then he suddenly spurts up any slope we are on and in Javier Ares’s voice begins to relay an assault that will take him all by himself to the top. And he leaves me behind, in space and in time, which is all as it should be given that I am a father. And I know who I am then and give thanks.