Adam Zagajewski, a High Road

“Zagajewsky never spoke with second-hand knowledge, he did not accept any inherited view: he rethought it all himself, and that is why he is so comfortable talking in his poems about evenings, clouds, meadows and birds”

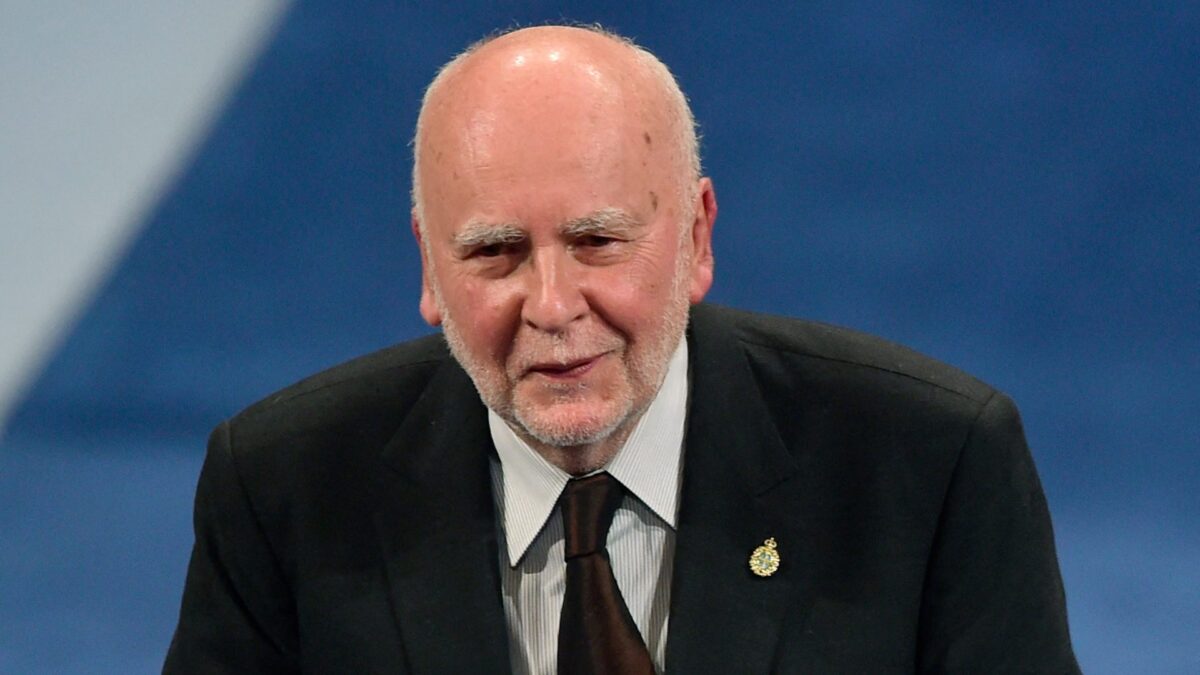

Miguel Riopa | AFP

There are few people we have read or heard express more elegant, exact and measured opinions about poetry than Adam Zagajewsky, to the point that we might think that, more than an outstanding poet which he also was, the man who died yesterday evening in Krakow, was also an extremely gifted thinker about poetry, a highly inspired essayist, and a very sensitive and intelligent reader.

His inspiration was, moreover, an ancient one: in his presence one genuinely he was standing before someone who had acquired true wisdom, as if attained in the course of various lives, weathered and refined thoughout the generations, which was certainly owing to his extraordinary empathy with other times and even with other worlds (that poetry comes from another world is what he unabashedly professes in one of his essays in Two Cities). His reading of Rilke, for example, is overwhelming, and he takes advantage of it to conduct a good overview of other great poets of the past century, over all of whom he has keen insight, an original and penetrating opinion. Zagajewsky never spoke with second-hand knowledge, he did not accept any inherited view: he rethought it all himself, and that is why he is so comfortable talking in his poems about evenings, clouds, meadows and birds: elements that contemporary poetry shies from, and disdains as trite, are reformulated by him and renovated, in that mixture of tradition and innovation, past and future, that is the poetry that matters to us.

He insisted that poetry was not to seek beauty but rather truth, and that beauty, if it comes, will come as something added on, by extension, as a consequence. But that truth is the indispensable core of the poetic is one of his most recurrent considerations, and it also is unmodern in a time that pulls an odd face as soon as the concept of “truth” makes an appearance. Sensibly spiritual, a believer in the natural and essential goodness of life despite having suffered serious historical reverses, he was also mistrustful of irony, and regarded its current abuse as a poetic device as something brutal, almost desperate, insofar as it is always a distortion of a reality that could, why not, be observed with a little more love.

Truth, goodness, life, love…What are we poets if we can get to the point that we are capable of fearing words like these? What have we become or in whose service are we if we prefer to avoid these words out of fear of being singled out by those who most need them? In the words and reflection of Adam Zagajewski, always spoken unshrilly, there was always that “defense of fervor”, to which he devoted an invincible essay, the conviction that beauty will always be more “scandalous” than provocation, more effective and, it goes without saying, more lasting. He knew that there was no better way to seek originality than to go for a walk or reread the great poets, observe the trees, and think of History in a spirit almost of charity. He said it in a poem from Return (translated as Regreso by Xavier Farré): “Poetry is the search for splendor./Poetry is the high road/ that takes us to the most distant”.

In his acceptance speech for the Princess of Asturias Prize in 2017 he returned to the idea of the presence everywhere of the good; he wanted to underline the idea that poetry always helps us find that small or great treasure of good that is always present, even in the most adverse circumstances, and to which we can always cling. But he also spoke of the complexity of the world, something to which poetry must always be attentive, and with these luminous words of his we wish to end, lamenting the death of one who, still relatively young, had so much to go on teaching us: “We discovered the duality of the world: on the one hand, imagination; on the other hand, the obstinate reality of a November morning when the leaves had already fallen from the trees. For a long time, I did not know which was more important: what exists or what does not exist? […] It took me many years to understand that we must take into account both sides of this unequal dualism; because we live in an eternal state of ambivalence, we cannot forget the suffering of persons and animals, nor forget evil, which is much more tenacious and cunning than the dreams we pursue. We cannot forget evil, injustice which continually changes shape, the things that perish, but neither can we forget happiness….” (from the translation by Paul Barnes).