Trump, Venezuela and the Price of Collapse

“Venezuela cannot pay without producing, and it cannot produce without massive investment. Its oil industry has been devastated”

Ilustration by Alejandra Svriz

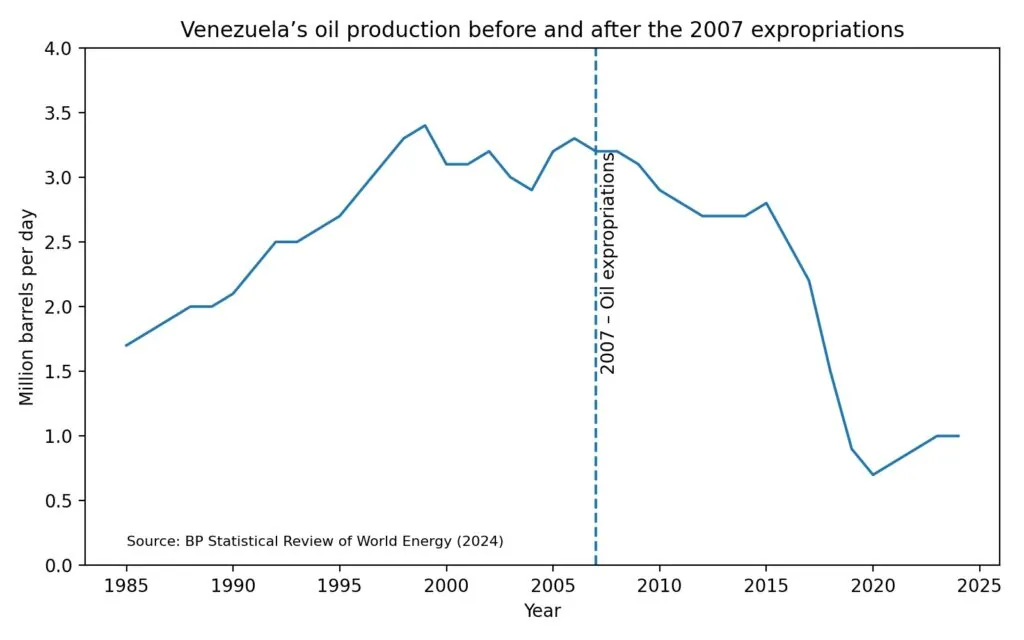

When Donald Trump says that Venezuela “owes” money to American interests, he is not referring to conventional sovereign debt or to pending state transfers. He is pointing—loosely but not arbitrarily—to a set of unresolved economic liabilities rooted in the nationalisations launched by Hugo Chávez in 2007: asset seizures carried out without effective compensation, adverse international arbitration awards, unpaid revenues to foreign partners, and the loss of operational control by international oil companies in Venezuela’s energy sector.

The language is political rather than legal. Yet the liabilities are real, and they continue to condition any credible attempt at Venezuela’s financial normalisation.

At the core of the problem lie international arbitration awards issued by tribunals such as ICSID following the dismantling of the contractual framework established during the oil opening of the 1990s. These awards are not financial instruments but enforceable judicial claims, often enjoying priority status and capable of being executed against strategic assets abroad.

A crucial nuance is frequently overlooked. In many cases, tribunals substantially reduced the amounts initially claimed. Final awards were often far lower than headline figures after annulment proceedings, offsets and parallel settlements. The liabilities were narrowed—but not eliminated.

Today, sector analysts estimate that the combination of outstanding arbitration awards, accrued interest and unpaid revenues owed to American companies as a result of the 2007 expropriations and PDVSA’s operational collapse amounts to between $20bn and $40bn, depending on scope and methodology. This is not marginal exposure. It is systemic.

The largest single case is ConocoPhillips, which holds an arbitration award of approximately $8.7bn, issued by ICSID in 2019 and confirmed in 2025 after Venezuela’s annulment request was dismissed. Interest and procedural costs further increase the amount potentially enforceable in ongoing execution proceedings across multiple jurisdictions. Other cases, such as ExxonMobil, ended with significantly lower net outcomes after complex litigation and offsets.

Beyond arbitration lies a quieter but structurally important front: unpaid revenues to foreign partners that continued operating in mixed ventures where PDVSA retained majority ownership. Companies such as Chevron, Repsol and ENI did not lose ownership of oil reserves, but they did stop being paid once Venezuela’s state oil company entered technical insolvency and ceased to meet its contractual obligations.

From an economic perspective, what matters is not only the size of these liabilities, but their enforceability. US courts have recognised PDVSA as an alter ego of the Venezuelan state, opening the door to asset seizures—most notably Citgo. This explains why control over cash flows has become central. It is not ideological. It is legal.

Here lies the constraint rarely acknowledged in public debate: Venezuela cannot pay without producing, and it cannot produce without massive investment. Its oil industry has been devastated by years of underinvestment, corruption and ideological management. There is no oil revenue to extract without first rebuilding fields, transport infrastructure, refining capacity, the electricity grid and human capital.

Investment, however, depends on more than expected returns. It depends on legal and political security. No major international oil company—and certainly no American one—will commit long-term capital in a jurisdiction with a recent history of expropriation and unilateral contract breaches without extraordinary guarantees of contractual stability, asset protection and institutional predictability.

From this perspective, Washington’s emphasis on revenue control, supervision and a tightly conditioned political framework reflects not only a recovery strategy, but a deliberate effort to minimise sovereign risk. For investors, the question is not merely how much oil can be produced, but under what rules and for how long.

This logic also explains why the US approach appears to prioritise control before normalisation. In environments of deep institutional collapse, foreign direct investment arrives only when the legal framework is perceived as exceptionally secure—even if that requires transitional arrangements that sit uneasily with classical notions of sovereignty.

Political rhetoric has been blunter. In December, Trump and allies such as Marco Rubio spoke of oil having been “stolen”. The phrase was effective, but technically imprecise. It prompted a response from Venezuelan oil executive and former Pedro Mario Burelli, who noted that while contracts were forcibly restructured between 2006 and 2007, no agreement ever transferred ownership of subsoil hydrocarbons to private operators. The dispute is contractual and financial, not colonial.

Nor should Venezuela’s recent past be sanitised. During years of isolation, the regime pledged resources and future revenues to China, Russia and Iran through non-transparent oil-for-loans arrangements, discretionary financing schemes and de facto concessions that failed to strengthen the state or benefit the population. Environmental devastation, the destruction of PDVSA and mass impoverishment were the result. The plunder already happened.

Against this backdrop, the energy framework announced by the United States formalises an economic reality rather than inventing one. Oil revenues will be channelled through US-controlled accounts and directed primarily towards investment and critical infrastructure, as outlined in the US government’s official fact sheet. This is a structural response to economic and productive collapse on a national scale.

Trump’s interview with The New York Times on Thursday sharpened the tone. He spoke openly of prolonged US oversight and acknowledged that restoring Venezuela’s oil sector will take years. The rhetoric hardened. The arithmetic did not change.

The debate, therefore, is not whether Venezuela’s collapse explains external intervention. It does. The question is whether that explanation becomes an absolute justification. Distinguishing between explanation and legitimisation is indispensable for rigorous analysis.